In this post, you will learn about the associations that are connected to coronavirus headlines and images, ultimately making content more shareable and viral.

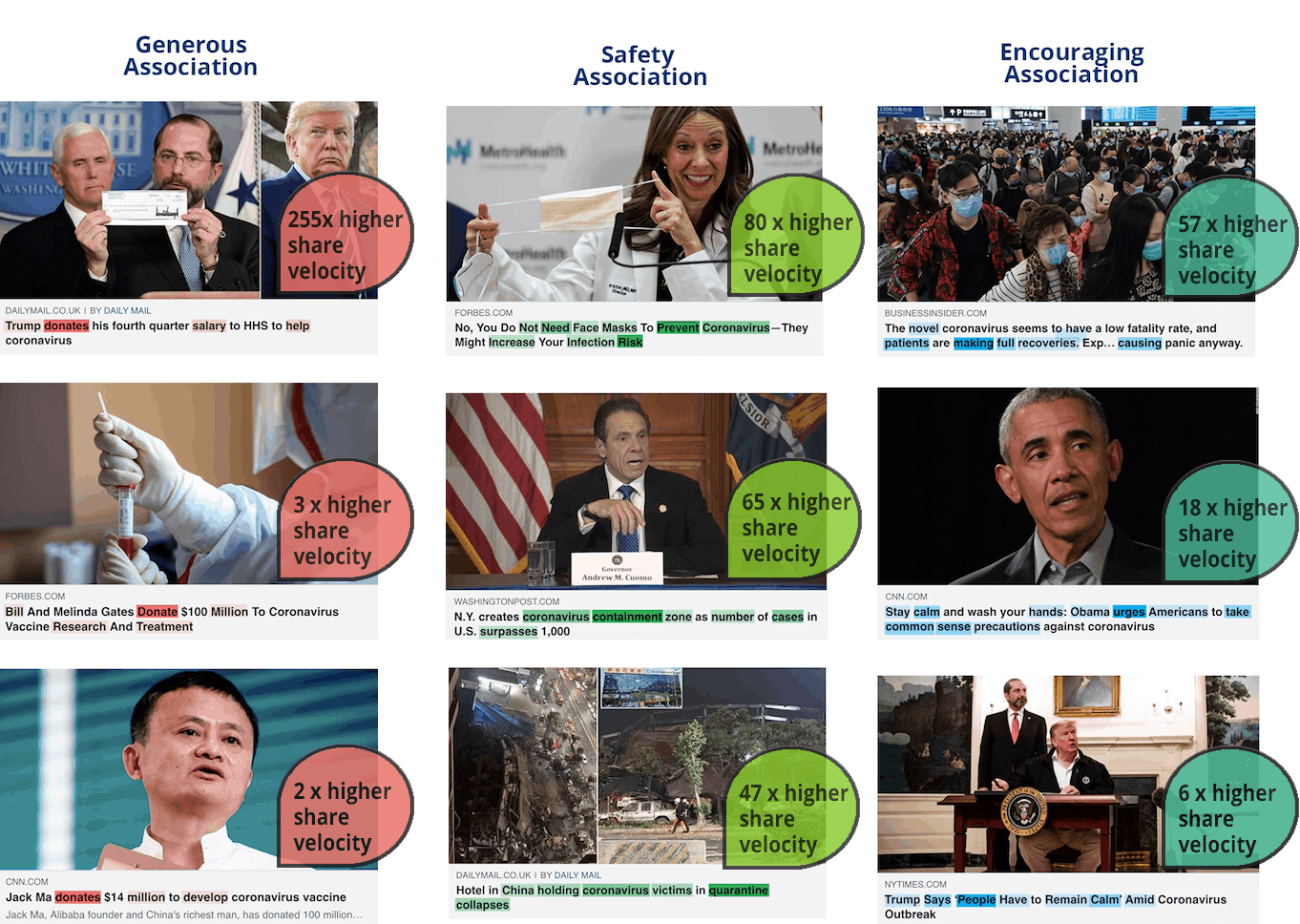

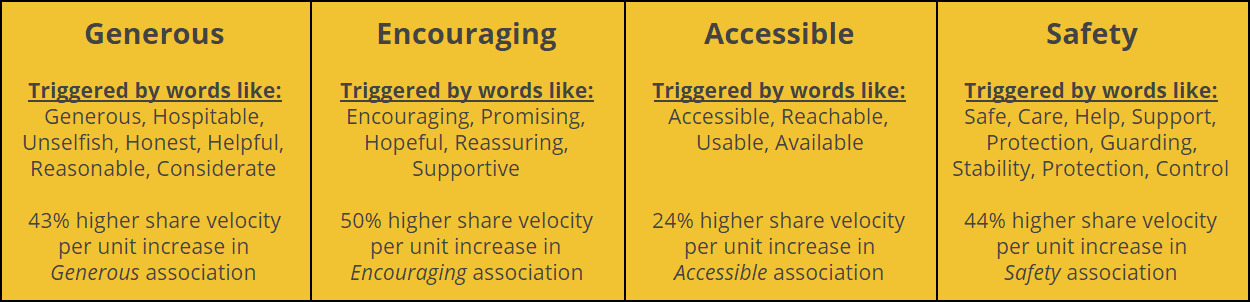

For example, Headlines that talk about people donating money for fighting the coronavirus, experts giving advice on how to be safe, answers to questions regarding the accessibility of essential goods and services. The message doesn’t need to be positive, instead, content that addresses these topics, in general, is shared more.

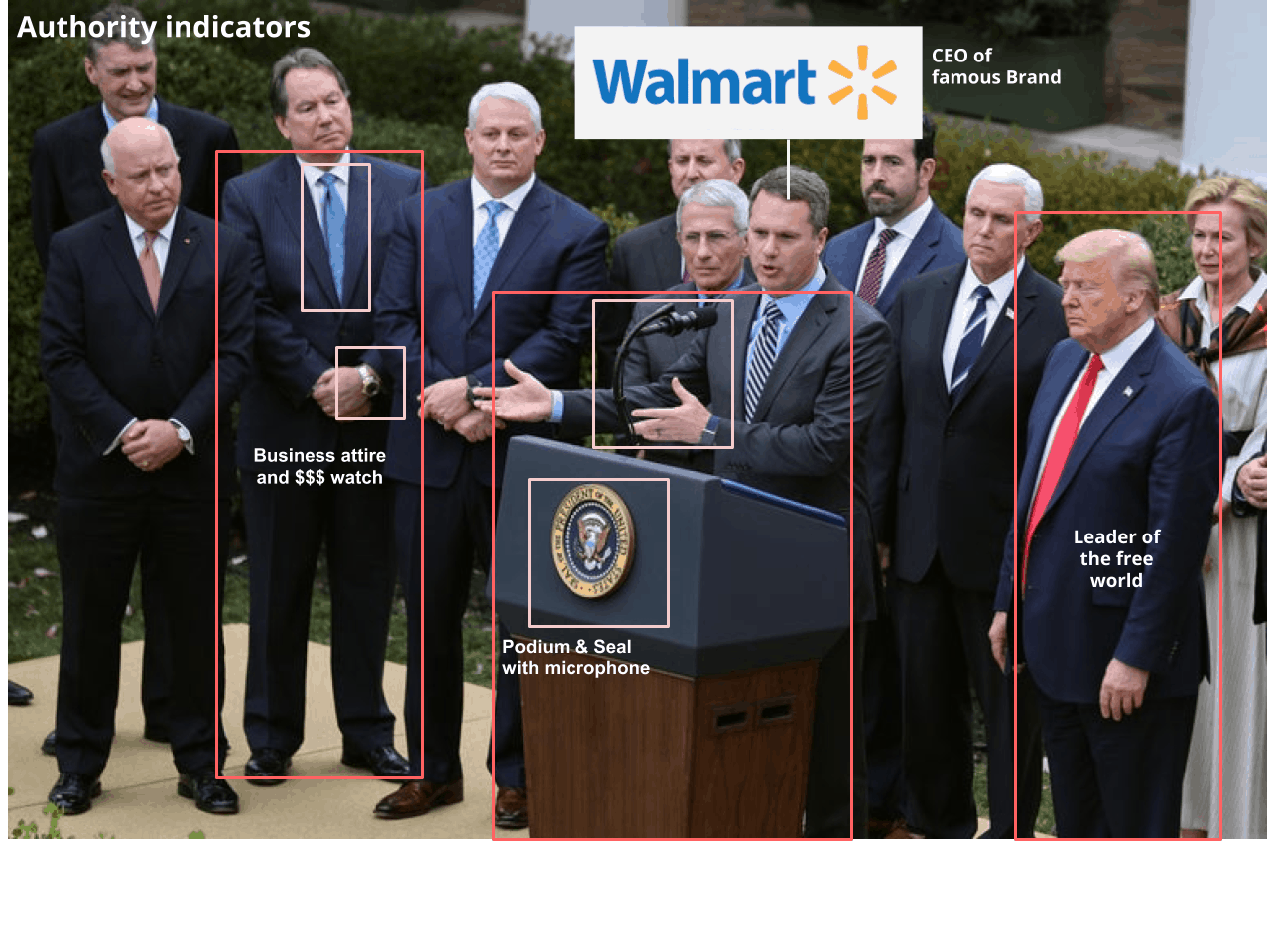

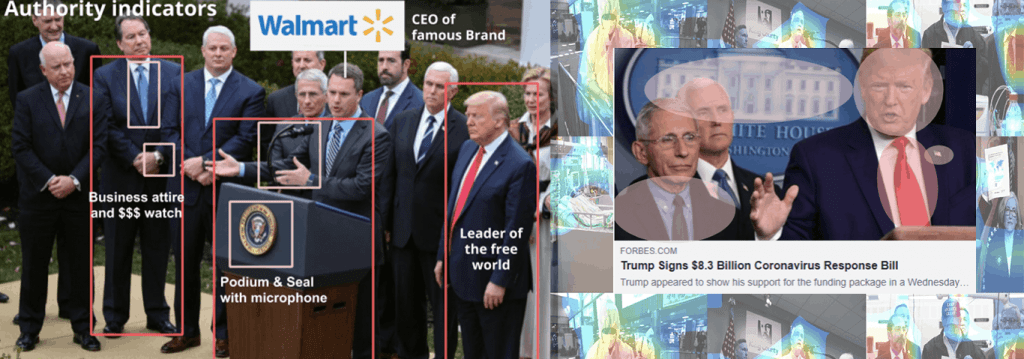

Pictures in which people are wearing format clothes, white lab coats or other symbols of status and expertise were shared more. We believe that in times of uncertainty, people look for reassurance and clarity from people who they perceive to be in charge. Indicators of authority are an efficient mental shortcut people use to accept information from that source.

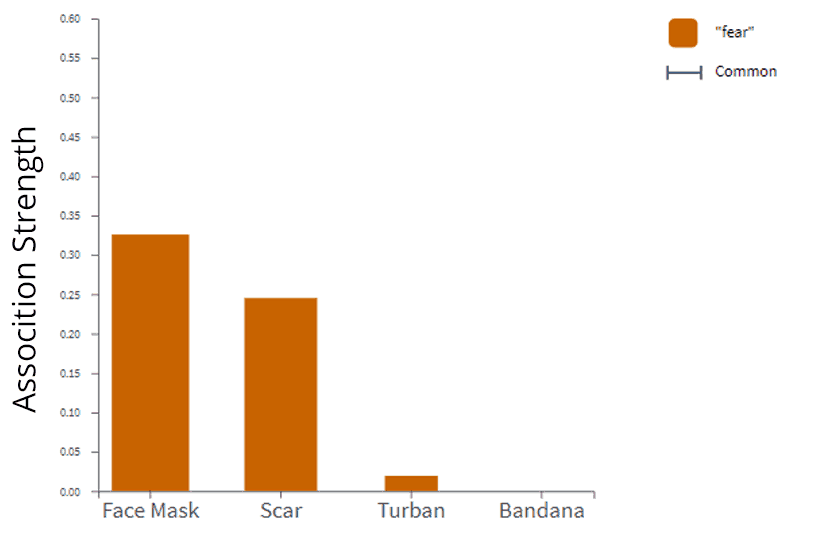

We believe that face mask wearers are seen as being sick and thus pose a risk that needs to be avoided. Face masks are also associated with “fear” in the English language.

Check out the rest of the analysis to understand why we believe that, things that appear to threaten or support “the tribe” are shared more.

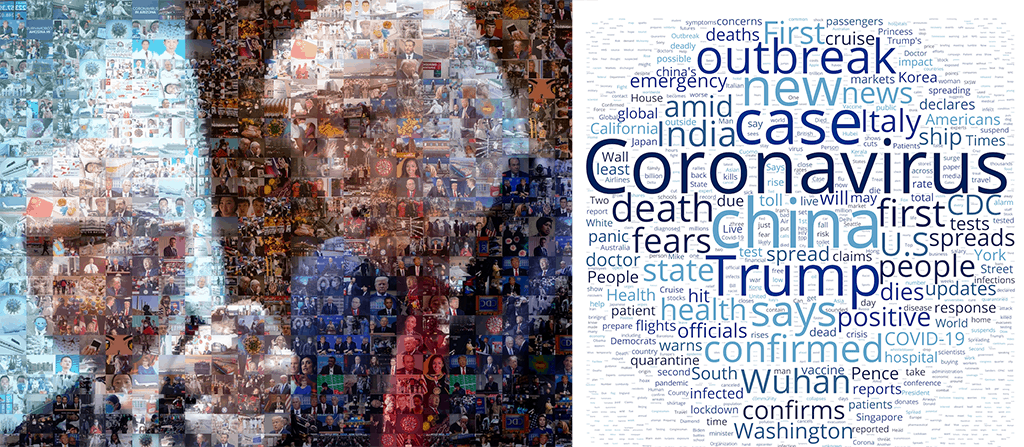

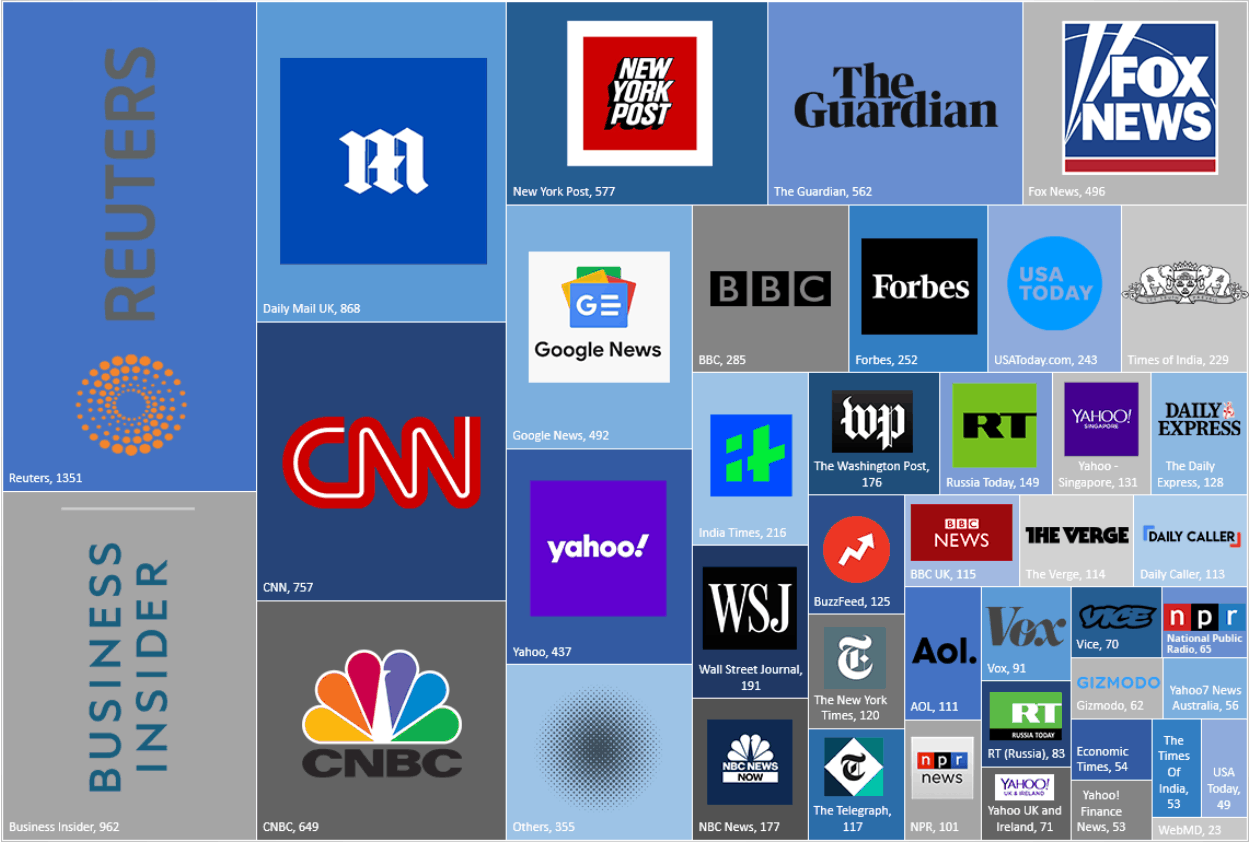

We looked at 11.333 headlines and images from western news websites, published between the fifth of December 2019 and 11th of March 2020, using the Aylien News API.

To make shareability between news sources comparable, we calculated “share velocity”. To illustrate, a news article with a share velocity of 5, is shared 5 times faster than a typical article on that site.

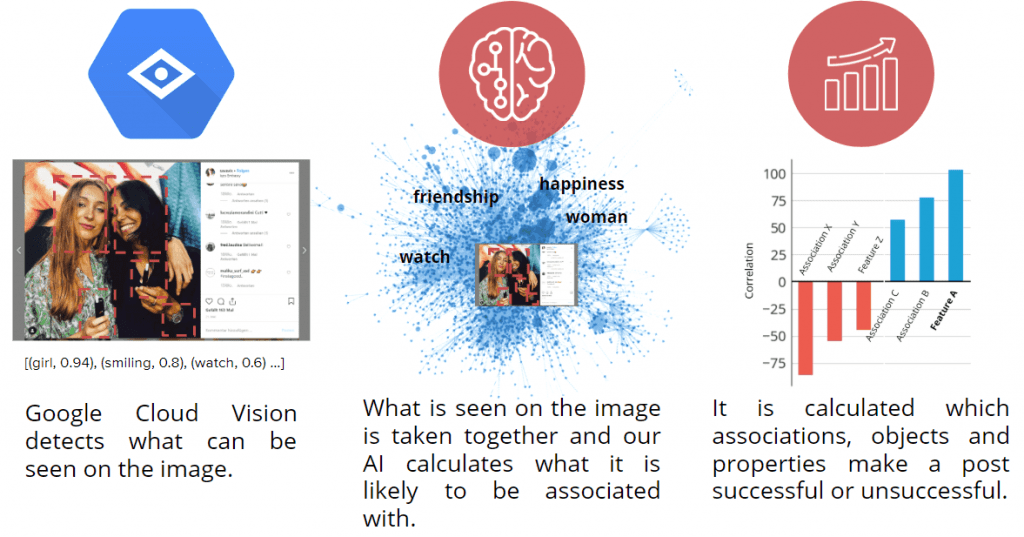

We then used a variety of methods to calculate the relationship between associations and the number of shares the content received.

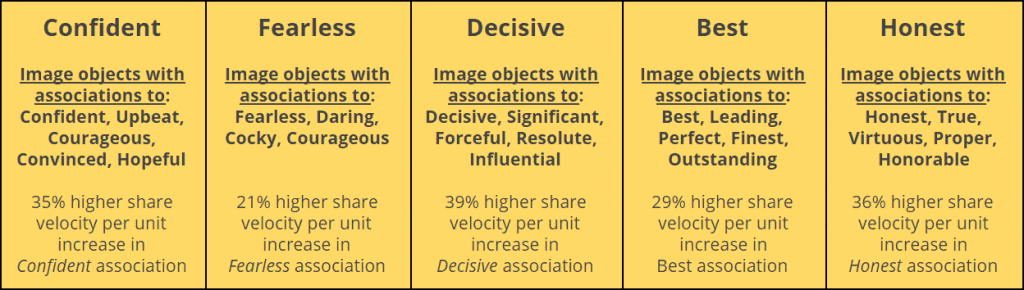

This means that more viral headlines featured one or several of these associations.

While there are multiple drivers of a topic’s virality, we find that the strongest correlates are themselves positive. But that alone may be misleading.

Many of the headlines evoke the potential for our safety being under threat or talk about medical equipment not being accessible. So while the topics themselves have predominantly positive associations, the reason why they are connected to more shares may very well be because the topic is of high relevance overall.

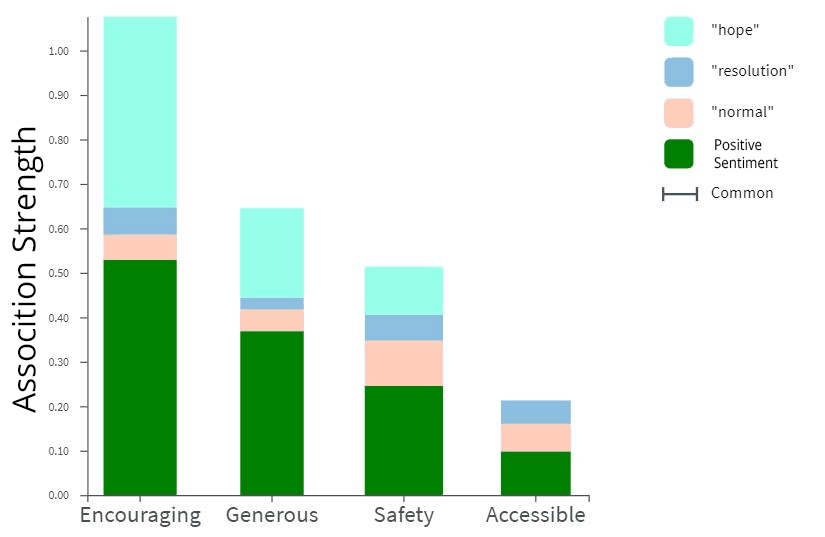

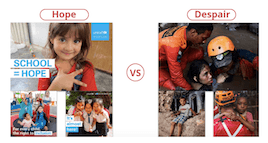

To test this assumption, we analyzed whether Encouraging words are related to words like hope and normal or resolution. As you can see in the image below, those words are indeed highly related.

Exploring what drives the viral text associations.

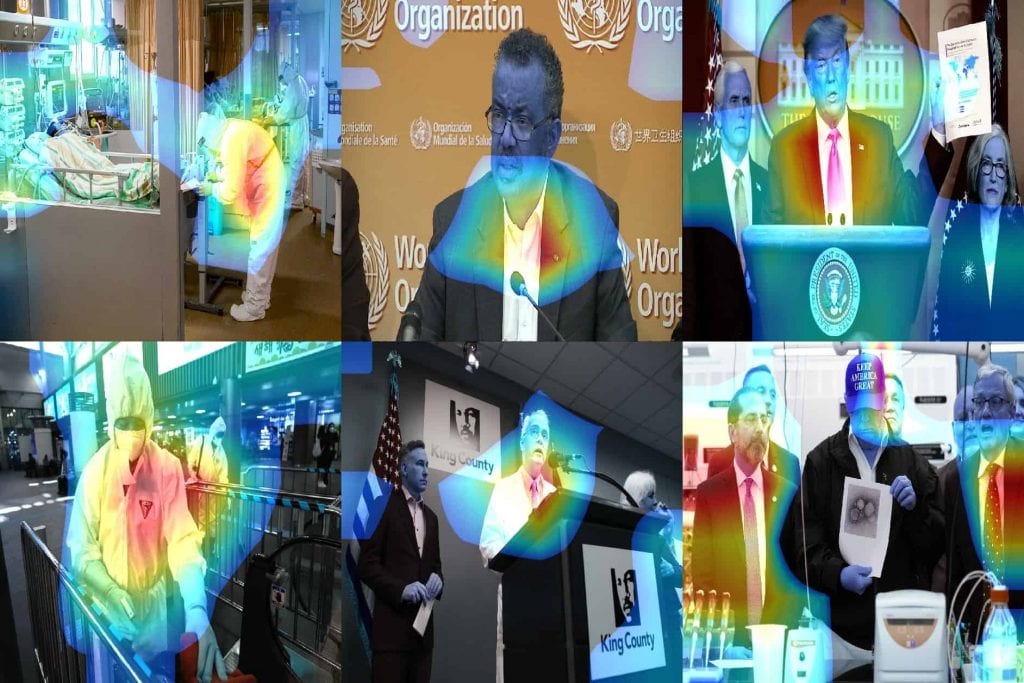

The parts of the images that made the neural network trigger success, showed people in formal outfits. This is in line with a well known social influence principle in psychology, appeal from authority.

Appeal from authority means that people search for indications of expertise, such as titles and uniforms, lab coats and suits. Once such indicators are detected, people are more likely to take the depicted person’s opinion seriously.

In our analysis, content that depicted authority figures were shared more often. Therefore, when the state or journalists want to spread health information more effectively, we recommend using authority indicators. To name a few: The name of a respected institute or university, people wearing suit and tie, physicians wearing lab coats, certificates, and logos of well-known brands.

Trump’s press conference on 13th March 2020 featured well-dressed CEOs of large brands. A quick glance at the picture below shows several cues of authority that shape people’s understanding of how trustworthy the information they are getting might be.

We also looked at the objects identified on the more shareable images. The associations of objects on the image, with a strong relationship with more shares, were:

In line with the heatmap analysis, we find associations relating to authority (Confidence, Fearlessness, Decisive etc.) to be correlated with more success.

Image with strong “Decisive” associations (Objects: White House, suits, red tie, Donald Trump, flag.)

Note that we are talking about associations here. A headline like “all confidence is lost, the best scientists have failed us, and we honestly don’t know what to do now” would likely be shared as well, as it is associated with confidence, fear, and honesty.

The factors behind sharing coronavirus content are related to the topics that are of the highest relevance right now. It is the relationship between association and shareability that content writers should mind, to understand what content is more likely to be shared.

Now we turn our attention to factors related to below-average shareability.

What group of people do we associate with the coronavirus? What do we think when we see someone wearing a head mask?

On February 11th, 2020, the WHO announced that the 2019 novel coronavirus would thereon be referred to as COVID-19. The current Director-General, Tedros Adhanom, explained how the WHO followed the guidelines to ensure the name does not refer to a geographic location, an animal, an individual or a group of people.

In spite of this effort, the reports on racially motivated attacks and acts of prejudice against people of Asian descent have spiked in the Western world.

But, how can this negative social attention be identified and pinpointed in the digital world?

Our heatmap analysis shows that the image area predictive of below-average shareability depicts people of East-Asian descent wearing face masks.

Another notion to explore here are the associations that people hold for face masks. The technology we have developed for our software is able to predict what associations people hold for any word or topic. Looking at the results, we found a strong association between face masks and fear:

The association with Face Mask and Fear is considerably higher than it is for other head/facial garments like Turban and Bandana.

This could perhaps be understood through the assumption that the face mask wearer might be sick and thus pose danger. While the reason behind wearing a face mask might indeed be illness, many healthy people chose to wear it in order to protect themselves from infections. Such nuances, however, are often not taken into account when anxiety levels are high.

We analyzed thousands of Coronavirus headlines and images about the coronavirus outbreak. Using machine learning, word embeddings and neural network activation mapping we determined the factors connected to higher shareability of coronavirus related content.

Taking a bird’s eye view, we found:

Authority is key in times of uncertainty: Shareability of image content appears to be linked to indicators of authority and status. Pictures of people in formal attire, suits, and lab coats, were shared more often than those with people in casual clothing.

We suggest that in times of uncertainty, people look for reassurance and clarity from people who they perceive to be in charge. Indicators of authority are an efficient mental shortcut people use to accept information from that source.

Hope for the tribe being strong: News about people who are supporting the community, e.g. by donating money or pledging to support initiatives, are like beacons of hope in dark times. Since humans are a species that survives best when acting as a group, seeing people who put the needs of the community above their own is a powerful social signal.

We believe that this communicates that there are still resources to be shared, that cooperation is still possible and that there is hope that things will be better.

Hope can be a powerful driver. Good leaders communicate difficult topics with honesty and ensure that people still feel like they belong to a united community. A community that can come together in hours of need to stand as one.

With dark topics on everyone’s mind, people share information that not only informs about the situation but also helps answer the question of how to feel right now.

In times of trouble, people are likely looking for want certainty. We believe that news articles that carry authority, depict the better side of humanity, and encourage a notion of hope and unity. Reaching more people is crucial.

Convincing people that avoiding social contacts or reducing it to the minimum to slow the spreading of the disease is crucial for our society right now. However, there are still many out there not convinced this is necessary or believing they are invincible.

Remember, your writing can make a difference in how people feel, think and act. Use words and images wisely.

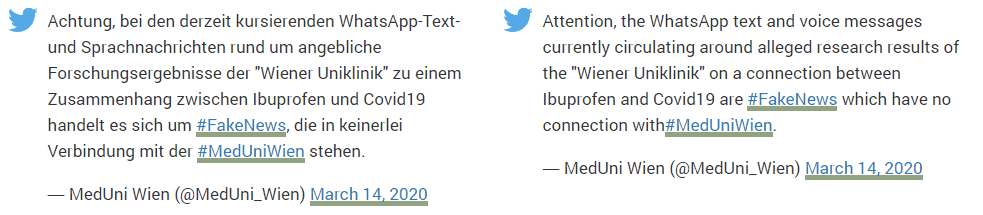

The same principles that lead to more shares for real news can also be used to spread fake news. For example, a WhatsApp message that cites the University of Vienna (appeal to authority) in which the use of Ibuprophene is discouraged, was shared thousands of times even though it was completely fake.

This analysis was the joint effort of the Data Science and content team at NEURO FLASH.